Review of Watership Down

/ Today I assigned my nine-year-old son, Noah, to write a short review of the book he’d just finished. I explained that this wasn’t just busywork. It’s actually a good way to collect one’s thoughts about a book after finishing it.

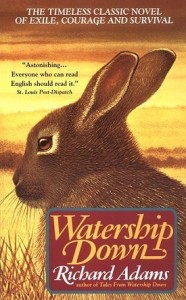

Well, tonight I finished Richard Adams’ Watership Down, a book that had been on my “I really should have read that a long time ago” list for many years. I guess it’s time to walk my talk.

Today I assigned my nine-year-old son, Noah, to write a short review of the book he’d just finished. I explained that this wasn’t just busywork. It’s actually a good way to collect one’s thoughts about a book after finishing it.

Well, tonight I finished Richard Adams’ Watership Down, a book that had been on my “I really should have read that a long time ago” list for many years. I guess it’s time to walk my talk.

If you are one of the three or four people in the English-speaking world who, like me, managed to miss this book, allow me to give you the basics. It’s about rabbits. It’s a remarkably subtle blend of anthropomorphization and well-researched naturalism. It draws heavily on great human epics about heroes and journeys and battles. Essentially, a character named Fiver is Cassandra (the character in Greek mythology cursed to always tell the truth but never be believed), but his brother, Hazel, does believe him and takes a group of rabbits on a journey. Hazel turns out to be Odysseus, only instead of returning from a war to his beloved wife, he’s using clever tricks to get his rabbits to a new warren. Then there’s Bigwig, the old warrior who is brave enough to stand up to the monstrous tyrant who wants to destroy the new warren. I guess that makes him like Achilles or Beowulf, but in his defense of the warren on Watership Down, he’s more like Hector bravely willing to give his life for Troy and his brother’s honor. No, that’s not quite right, either. Anyway, they are all great characters who deserve to have their stories told to many generations of rabbits and humans.

One of the things that struck me was Richard Adams’ insistence that the book is not an allegory for any human events. I think he’s being totally honest that he didn’t intend for any allegory, but that doesn’t mean that one doesn’t exist. Perhaps it’s a testament to the human need to create stories, just as the rabbits of Watership Down tell one another stories (beautiful stories interspersed throughout the book), that we connect this story to our own experience whether the author intends for us to do so or not. When General Woundwart, the leader of the opposing warren, comes to Watership Down and rejects the offer of peace out of fear and obsession, I couldn’t help but think of times I’ve made similar (though less deadly) blunders based on pride and a need to save face. I also thought of all the human wars started due to the same base motives. It’s not comfortable to discover a connection between my own failed attempts to maintain control in situations where I should have sought a win-win and times when whole nations flung themselves at one another because leaders made the same blunders on catastrophic scales, but that’s just the kind of connection that these non-allegory epic tales of adventure can produce if we are willing to let them.

Though I told Noah it was fine to spoil the ending in his own notes, I won’t do it here in a public forum. Suffice it to say that the ending was entirely satisfactory in that it resolved all the issues but made me wish Hazel, Fiver, and Bigwig could get caught up in another series of adventures so that I could spend more time with them.

The writing is masterful. It’s always difficult to know how much to describe the natural world in a human story, and too often writers allow themselves to wax on and on about the movements of clouds and the play of sunlight through leaves fluttering in the wind without any thought to the fact that the human characters in the story don’t give a flying photon, and thus the readers don’t either. In general, these are prime examples of the darlings that must be killed. But in Watership Down, the descriptions of the natural world are direct products of the characters’ interests and their immediate sensory impressions. Just as a description of the direction of the wind is entirely relevant in a story about sailing ships, a description of scents on a breeze really matters in this book because it matters to the rabbits. That’s a good reminder for writers; if the reader cares about the characters, he/she will care about what the characters care about. But if you spend too much time on trivialities that are unimportant to the characters, the reader will not only lose interest in the story, but may cease to like the characters, too. I’ll be giving that more thought as I revise thanks to this novel.

Do not continue to make the mistake I made for so many years. Grab a copy of Watership Down posthaste.

...after you get a copy of The Sum of Our Gods, of course.